전시 EXHIBITION

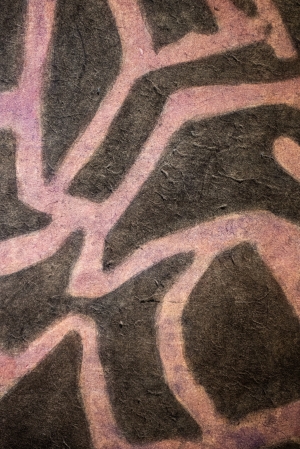

나무껍질을 입는 몸

서인혜 <나무껍질을 입는 몸>

대전 지역 노인들의 몸빼 바지 속 무늬와 주름이 그려내는 여성의 노동과 삶에 대한 이야기

서인혜는 일상생활과 밀접하게 관계를 가지는 의복에서 사용되는 장식이나 무늬들을 통해 그들의 몸에 새겨진 습관, 축적된 시간성을 나타내는 작업을 한다. 이번 프로젝트에서는 대전 지역에서 수집한 노인들의 몸빼 바지 속 무늬와 주름이 그려내는 여성의 노동과 삶에 대한 이야기를 풀어낸다.

<작가 노트 中>

나는 사물의 표면을 통해 보이지 않는 현상이나 그것에 내재된 단면을 보려 한다. 지난 몇 년간 익숙한 영역으로부터 벗어나 여러 지역을 이동하면서 느꼈던 사물의 표면적 감각은 낯설고 새로웠다. 주변 환경을 구성하는 사물의 형태와 색, 질감 등의 속성과 그것이 놓인 방식을 세심하게 관찰하게 되었다.

서울에서 쉽게 보지 못하는 지역 여성노인들이 즐겨 입는 몸빼바지의 장식적인 패턴과 무늬가 시각적인 즐거움으로 다가오게 되었고, 이를 한 사람의 정체성을 구성하는 독립적인 기호 시스템으로 인식하게 되었다. 일상생활에서 복식은 항상 껍질 그 이상이며, 몸의 사적인 경험이자 공적인 표시가 된다. 옷의 표면이 어떻게 인식되고 몸에 작용하여, 개인의 행동이 몸과 관련한 하나의 실천이 되도록 하는가에 관하여 조사하게 되었다.

대전 지역의 여성 노인들을 대상으로 올 초부터 관계를 맺고 인터뷰를 진행하였다. 인터뷰는 대전지역에서 보호수로 지정된 나무가 있는 괴곡동과 대사동을 중심으로 이루어졌다. 인터뷰의 기준을 나무에서부터 출발한 까닭은 껍질이 벗겨진 오래된 나무의 표면과 나이든 인간의 가죽 사이의 유사성을 발견하였기 때문이었다. 신체 표면에서 일어나는 몸의 위축과 노화의 과정을 통해 자연의 내재된 질서와 시간성에 적극 동참하고 있는 인간의 속성을 발견하였고, 자연과 인간과의 상호작용을 직조하고자 하였다.

몸빼 12곡병

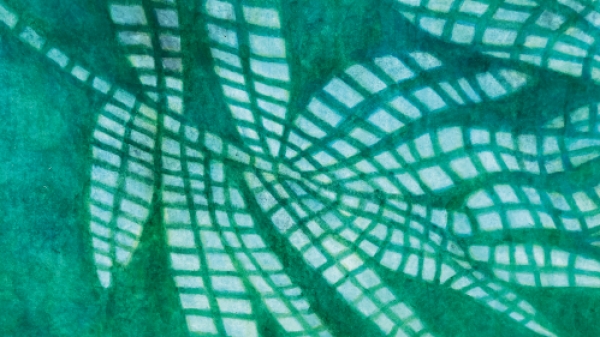

보이지 않는 틀과 코드화된 몸빼 무늬와 패턴을 가지고 삼차원의 장식적 장면으로 빚어내고자 하였다. 12개의 몸빼 무늬를 엮어 의례나 제사에 쓰이는 병풍의 형태로 제작하였다. 그리고 그 표면 뒤에는 개별적이고 파편적인 그들의 이야기를 복수의 화자, 복수의 목소리를 통해 전달하고자 하였다.

자연의 시간과 섭리에 인간은 순응하며 살아가지만, 인간과 자연사이의 구분은 노동에서 시작이 된다. 노동을 하기 위해 입는 몸빼 바지의 장식적 무늬를 통해 자연과 인간, 세속성과 신성함, 그 경계에서 펼쳐질 수 있는 껍질막을 상상해보았다.

-

나무 껍질을 입는 몸

이문정 (미술평론가, 연구소 리포에틱 대표)

전시장에 들어서자 커다란 영상이 가장 먼저 눈에 들어온다. 클로즈업된 할머니의 얼굴, 거칠어 보이지만 온기가 느껴지는 나무가 나란히 모습을 드러낸다. 반대편에는 균형을 맞추듯 병풍을 연상시키는 설치물이 마주 보고 서 있다. 화려하지만 은근한 색채의 문양이 가득하다.안으로 조금 더 들어가 본다. 그 정체는 모호하지만 거친 표피만은 선명한 나무조형물을 전환점 삼아 우측으로 돌아서니 오랜 시간을 품은, 누군가의 시간과 기억이 담긴 사진과 물건들이 발견된다. 아늑한 방을 구경하는 기분이다. 어둡지만 따뜻한 불빛은 전시장의 분위기를 고요하게 이끈다. 한적하고 느긋하다. 무슨 이유인지 해가 질 무렵의 풍경이 떠오른다.

전시 ‘나무 껍질을 입는 몸’(2020)에서 서인혜는 세월을 담아내는 할머니의 피부와 나무 껍질, 종이를 개념적으로 엮어 인간의 삶과 생명의 기운, 자연의 섭리를 고민했던 자신의 여정을 보여준다.

작업의 시작은 작가의 어머니였다. 작가는 음식점을 운영하던 어머니가 매일 김치를 담그는 모습을 지켜보며 여성의 노동에 대해 생각하기 시작했다. 가족을 위해 묵묵히 일하는 어머니. 어머니를 생각하다 어머니의 어머니인 할머니가 떠올랐다. 그렇게 이어진 작업. 한지와 천에 붉은색을 입힌 뒤 설치한 <버무려진 이야기>(2017), <버무려진>(2018), 그리고 영상 작업인 <버무려진 노동>(2017), <열무>(2019)는 가정과 사회에서 요구하는 역할을 따르며 삶을 꾸려나가는 어머니의 노동을 담담한 어조로 보여주었다.

이후 서인혜는 오랫동안 노동해온 여성의 피부와 의복으로 시선을 돌렸고, 이때부터 할머니들이 입고 있는 옷의 문양이 작품에 등장하기 시작했다. 작가는 할머니들이 실제로 입고 있는 옷의 사진을 찍어 그것을 재현했는데, 사진을 찍는 과정에서 할머니들과 대화를 나눌 수 있었고 삶의 희로애락에 조금 더 가까이 갈 수 있었다. 그래서일까. 그 결과물인 <삼산 할매 가죽>(2019), <굳은살과 물렁막>(2019), <버무려진 막>(2019) 등의 작품에서는 한층 깊어진 시간의 층이 전달된다.

이번 전시에서 서인혜는 몸빼라고 불리는, 할머니들이 즐겨 입는 일바지의 문양이 그려진 <몸빼12곡병>(2020)을 선보였다. 옷은 피부에 얹어진다. 또 하나의 피부와 같다. 피부로 대표되는 인간의 껍질. 그것은 생명을 담고 있으나 언젠가 생명의 기운을 놓칠 인간 몸의 은유이다. 시간의 흔적을 고스란히 보관하는 보물 상자이기도 하다. 작가는 굳은살이 박이고 주름이 생긴 할머니들의 손으로 대표되는, 다사다난했던 삶을 견뎌낸 인간의 피부가 오랫동안 살아온 나무의 껍질과 같다고 생각했다. 그래서 대전의 보호수가 있는 괴곡동과 대사동에 거주하는 할머니들을 만났고, 할머니들이 입고 있는 일바지의 문양을 수집했다.

이번에는 천이 아닌 한지에만 문양을 그렸다. 한지가 더 피부에 가까운 느낌을 주기 때문이다. 할머니들의 상징과 같은 일바지의 문양이 한지에 옮겨지고, 작가는 묵직한 시간을 품은 할머니의 피부를 담아내기 위해 한지의 표면이 일어날 정도로 여러 번 문질러 가며 색을 올렸다. 그런데 작가가 그려낸 문양의 색은 실제 옷보다 어둡다. 삶의 흔적이 묻어있는 일바지를 생각하며 그렸기 때문이다. 결과적으로 작가의 손길이 가면 갈수록 한지의 표면은 나무 껍질을 닮아갔다. 얼마의 시간이 흘렀을까. 작가는 일바지의 무늬로 그려낸 개인 삶의 역사화를 이용해 병풍을 만들었다. 병풍은 의례를 상징하는 사물이지만 그 스스로가 주인공이 되지는 않는다. 이런 이유로 작가는 병풍이 마치 어머니 같다고 느꼈다. 중요하지 않게 여겨지는 생활복이자 노동복인 일바지의 무늬가 그려진 병풍이 어떤 의미를 생성하게 될지 궁금한 마음도 있었다. 그렇게 노동과 의례, 일상과 비일상, 편안함과 엄숙함이 교차된다.

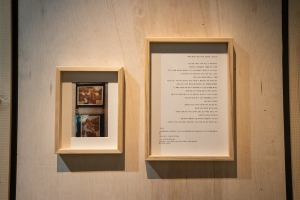

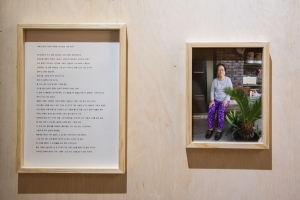

<몸빼12곡병>을 제작하면서 서인혜는 문양을 수집하는 데에만 집중하지 않았다. 쉽지 않은 과정이었으나 작가는 할머니들과 최대한 자주 만나 긴 시간 동안 대화를 나눴고 층층이 쌓인 삶의 기억 일부를 받아올 수 있었다. 그리고 그 결과물인 할머니들의 물건과 메모, 대화를 촬영한 동영상, 대화 내용을 적은 글이 병풍 뒤에 자리했다. 전시된 물건들은 자신의 기억을 관객에게 전하고, 자신도 또 하나의 기억을 저장하게 되었다.

할머니들이 전해주는 삶의 이야기는 우리가 기대하는 감정을 흠뻑 전달한다. 따뜻하다. 그리고 애틋하다. 이런 감정이 있는 그대로 전달되는 이유가 있다. 타인의 삶이 자신으로 인해 정형화되는 것을 경계하는 작가의 작업 태도 덕분이다. 서인혜는 할머니들과 만남을 가지면 가질수록 의도적으로 의도가 담기지 않은 대화를 나누려 노력했다. 대화하는 동안은 자신의 작업을 위한 만남이라는 사실을 잊으려 애썼다. 무엇보다 할머니들과 진심으로 교감하고 싶었고, 할머니들을 작업의 소재로 대상화하고 싶지 않았기 때문이다. 작가는 자신이 할머니들의삶 속으로 녹아들길 원했다. 그러다 보니 자연히 할머니들과의 대화를 촬영한 영상에는 작가가 자주 등장하여 소통이 일어나는 과정을 과장 없이 보여준다.

시간이 흐르면서 서인혜는 점점 한 인간으로서 할머니들의 삶을 바라볼 수 있게 되었다. 어머니의 노동에서 시작된 작업은 이제 인간 삶의 본질을 탐구하는 것으로 확장된다. 이 세상에 태어나 생각하고 느끼며 노동하고 소통하다 언젠가 세상을 떠나는 인간 존재에 대해 숙고하게 된 것이다. 『산해경山海經』에 나오는 웅상목雄常木에서 영감을 받아 만든 <웅상에서 나온 가죽>(2020)에서 확인할 수 있듯 작가는 아득한 옛날부터 전해져온 인간과 자연의 연결 고리를 추적하고 상상한다.

한편

불현듯이 떠오르는 질문이 있다. 먼 시간이 흘러 작가가 할머니의 나이가 되었을 때 괴곡동의 느티나무 앞에 서면 어떤 감정을 느낄까? 그때의 감흥은 작업에 어떻게 스며들까? 작가는 다음 작업에 자연 그리고 자연의 흐름 속에서 살아가는 사람들과의 교감을 어떻게 담아낼까? 인간 존재에 대해 어떤 질문을 던질까?

현재 작업에서 가장 중점을 두는 것이 무엇이냐는 질문에 작가는 “최종적으로 자연과 인간의 관계를 숙고하는 것”이라 답했다. 이는 작가가 할머니들과의 교감 속에서 잊고 있었던 인간의 삶을 아우르는 근원적인 자연의 질서와 원리를 기억해냈기 때문일 것이다. 숨을 가다듬고

Body Dressed in Tree Bark

Lee Moonjung (Art Critic and Director of Leepo?tique)

The first thing visitors see as they enter the exhibition hall is a large video screen. It shows the close-up face of an elderly woman and a tree that looks rough but emits warmth. On the opposite side stands an installation work that resembles a folding screen as if to balance with the video screen. It is full of brilliant patterns in subdued colors. Walking further into the hall and turning right from an obscure tree sculpture with rough but vivid skin, you can find old photographs and items carrying someone’s time and memories cherished for years. You may feel as if you are visiting a cozy room. The dim but warm light adds tranquility to the hall. You feel calm and relaxed. Somehow, it reminds you of the landscape around the time of sunset.

In her exhibition titled ‘Body Dressed in Tree Bark (2020),’ Seo In Hye shows her own itinerary of a journey in which she contemplated on the energy of human living and life as well as the provision of nature by conceptually linking the elderly woman’s skin, which carries her years, with tree bark and paper.

The artist’s work started from her mother. Looking at her mother who runs a restaurant making kimchi every day, she began pondering on women’s labor. Thinking about her mother led her to remember her maternal grandmother. Her thoughts progressed to installation works such as The Seasoned Story (2017) and The Seasoned (2018) created by coloring hanji (traditional Korean paper handmade from mulberry trees) and fabric in red, as well as to video works The Seasoned Labor (2017) and Young Radish Kimchi (2019), which plainly described the labor of a mother who manages life carrying out her role demanded by the family and society.

After that, the artist turned her eyes to the clothes and skin of women who have worked hard for years, and started to show the patterns from the clothes commonly worn by elderly women in her works. She took pictures of their clothes to reproduce them, chatting with the women while photographing them and getting a bit closer to the joys and sorrows of life in the process. Maybe that is why her resulting works such as Samsan Granny’s Skin (2019), Callus and Soft Skin (2019) and The Seasoned Skin (2019) present even deeper layers of time.

In the exhibition, Seo presented 12-piece Folding Screen of Momppae (2020) based on the patterns from loose work pants called momppae, which is commonly worn by elderly women. Clothes are worn on the skin. They are like additional skin. Skin represents the outer layer of human beings. It is a metaphor for human body that carries life but will lose the energy of life someday. It is also the treasure chest that stores the traces of time in their entirety. The artist felt that human skin, which has endured a lifetime of ups and downs and is represented by the callused and wrinkled hands of elderly women, resembles the bark of a tree that has lived on for a long time. That is why she met old women living in Goegok-dong and Daesa-dong where protected-trees are located and collected the patterns from the work pants they were wearing.

This time, she painted the patterns just on hanji, and not on fabric. It was because hanji feels more like the skin. After transferring the patterns from the pants on hanji, she applied colors rubbing the surface of the paper multiple times until it became fluffy, in an attempt to represent the skin of the old women carrying the heavy weight of time. But the colors of the patterns painted by the artist are darker than those of the actual pants, for she wanted to show work pants smeared with the traces of life. Thus, the longer she worked on the painting, the more the surface of the paper resembled tree bark. How much time passed? The artist created the folding screen by historicizing the lives of individuals based on the patterns from work pants. Folding screens symbolize rituals, but they don’t take the central spots. This is why the

artist felt that a folding screen is like a mother. She was also curious as to what kind of meanings the folding screen, showing the patterns from the pants that are worn both daily and for work, will generate. Likewise, the artwork represents labor and rituals, what is daily and what is non-daily, and comfort and solemnness intersecting with each other.

While working on 12-piece Folding Screen of Momppae, Seo did not just concentrate on collecting patterns. Although it wasn’t easy for her, she met the elderly women as often as possible, chatted with them and managed to gather some of their memories of lifetime piled up in numerous layers. As a result, personal items and memos of the elderly women as well as videos and transcripts of the conversations are exhibited at the back of the folding screen. The displayed items will convey their memories to the visitors and, in turn, the artist will also get another memory that

she will keep.

The stories of life from the elderly women deliver the sentiments that we expected in full. They are warm and affectionate. There’s a reason why these sentiments are transferred intact. It is thanks to the artist’s work attitude of taking precaution not to standardize other people’s lives based on her own view. As she continued meeting with the elderly women, she tried hard to avoid intentional conversations. While talking to them, she made efforts to forget that she was meeting them as part of her work. Above all, she wanted to sincerely sympathize with them and not to objectify them as the subjects of her work. She wanted herself to be absorbed in the women’s lives. Therefore, the artist often appears and communicates with them in the video of their conversations.

As time went by, Seo could manage to look at the lives of the elderly women as individual persons. Her work that started from her mother’s labor has extended to an exploration into the true nature of human life. It is a contemplation on the human existence that is born into the world, thinks, feels, works, communicates and then leaves the world. As exemplified by The Skin from Xiongchang tree (雄常) (2020) inspired by Xiongchang tree (雄常木) from ‘The Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經),’ the artist searches for and imagines the ancient link between human and nature.

Meanwhile, Da capo aria (2020) is another work that lets us witness the process in which the scope of her artistic thoughts broaden.

Questions arise suddenly. When, after a long time, the artist reaches the age of the elderly woman, what will she feel when she stands before the zelkova tree in Goegok-dong? How will the sensation permeate her work? How will she reflect her communion with nature and people living in the flow of nature to her next work? What kind of questions will she pose on human existence?

To the question of what she is focusing on most in her current work, the artist says that it is, ultimately, the contemplation on the relationship between nature and human. It may be because she remembered the underlying natural order and law of nature embracing human life, which she had forgotten, based on the communion with the elderly women. I breathe deeply, and look at the zelkova tree in Da capo aria. I can feel the flow of time that continues to be long. Life continues and flows on like that.

- 기간

- 2020-08-25 ~ 2020-09-06

- 관련행사