전시 EXHIBITION

특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체

-

특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체 (The Unspecific Identity of Specific Space)

-

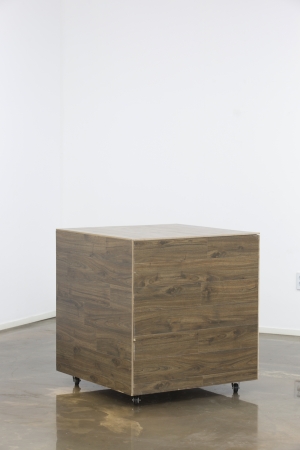

공간물체_03(Specific Space thing_03)

-

공간물체_03(Specific Space thing_03)

-

전시 전경

-

전시 전경

-

특별한 계단 (Specific Kind of Stairs)

-

특별한 큐브 (Specific Kind of Cube)

-

특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체

(The Unspecific Identity of Specific Space)

-

특별한 삼각형 (Specific Kind of Triangle)

-

특별한 입체도형 (Specific Kind of Solid Figure)

-

특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체 Act

-

특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체

고동환의 <특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체>는 우리가 집이라는 단어를 통해 일반적으로 떠올릴 수 있는 안정되고 견고한 이미지에서 탈피하려는 시도를 보여준다. 작가에게 집은 중요한 주제이자 소재이다. 집이라는 공간은 하나로 정의 할 수 없는 매우 복합적이고 개인적인 기억과 지각 그리고 암시들이 교체하는 특정한 장소이다. 이 특정한 시간과 공간에서 경험되는 구체적이면서 가장 개인적인 기억과 경험은 그 자체를 넘어서 집을 매우 특별하면서 또한 불특정하고 모호한 공간으로 만들고 있다.

-

나의 집 혹은 타인의 방

이진실 (독립큐레이터, 아그라파 소사이어티)

우유갑 같은 작은 집들이 도열해있다. 종이 박스로 접어 만든 이 집들은 펜으로 다채롭게 색칠된 채 옹기종기 모여있다. 멀리서 보면 귀엽고도 다정하다. 그러나 동화 같은 이 집에는 창문도 들어가는 입구도 없다.

기실 ‘집’이라는 주제는 아주 뻔한 상징의 기표이자, 누구나 자신의 서사를 투사할 수 있는 보편적인 메타포다. 그러나 다시 들여다보면 이 집이라는 것만큼 어렵고 난감한 주제가 따로 없다. 보통 ‘집’과 ‘방’은 공적 영역과 사적 영역을 분명히 구분하기 시작한 근대 시민사회의 출발과 더불어 문학과 예술의 무대에 올랐다. 19세기 말 부르주아 계층의 향수가 담긴 당대 예술들에서 집은 한 시대가 저물어가는 몰락의 이야기와 정서적 파편들이 널린 서정적 폐허였다. 20세기 들어서 집은 공적이라 할 수 있는 여러 활동과 관계로부터 도피할 수 있는 정체성의 마지막 피난처이자, 오로지 자신의 취향과 욕구와 습관 만을 투사할 수 있는 사적 공간이 된다. 한편으로, 그러나 중요하게도, 집은 여성들의 자리와 역할에 대한 이데올로기적 투쟁이 벌어지는 모순에 찬 전장이기도 했다. 우리는 헨리크 입센의 <인형의 집>과 버지니아 울프의 <자기만의 방>을 집에 대한 그러한 모순, 억압, 소망의 결정체로 떠올리곤 한다.

반면, 동시대를 살아가는 남성들에게 집이란 무엇일까? 한국 문학에서 본격적인 도시화와 산업 근대화 속에서 남성 가부장들의 소외와 공포를 다룬

최인호의 <타인의 방>이 떠오른다. 아파트라는 주거공간이 부상하고 핵가족의 분화 속에서 ‘내 쉴 곳’이라는 따뜻한 가정의 환상을 박탈당하는 남성적 소외와 왜소화, 사물화된 세계를 그린 단편 소설이다. 지금 한국의 남성들이 느끼는 정서(그것도 IMF 이후 대중매체에서 너무나 많이 드러내고 위로했던 정서)와 그리 먼 이야기는 아니지만 어쨌든 이 소설이 쓰여진 것은 1967년이다.

영국 유학을 거치고 고향집으로 돌아온 젊은 남성 작가가 강박적으로 만들어낸 이 입구도 창문도 없는 집들은 어떻게 읽어야 하는가? 어쩌면 여기에 심리적인 구조나 맥락을 읽어내고자 하는 것은 헛된 시도일지도 모른다. 작가는 마치 레고놀이에 푹 빠진 아이처럼 집을 다양한 색과 재료로 조립해보고 있고, 그 형태적 유희는 그다지 무거운 정서를 깔고 있지 않기 때문이다. 하지만 왜 하필 집인가? 고동환의 작업은 굉장히 제도사나 디자이너와 같은 태도로 조각과 평면으로 집을 만들어내는데, 그 집은 어떤 서사의 암시나 의미의 심도가 없는 듯 고도로 추상화된 형태로 제시된다. 육각면체에 삼각 지붕을 얹은 집의 기하학적 형태는 한국적 혹은 어느 지역적 특성이나 구체성 없이 보편적 개념만을 제시하듯 단조롭고 매끈하다. 집이라는 문자를 활용하는 방식도 유사하다. 집이라는 한글을 반복적으로 배열한 책이나 ‘Mi Casa’라는 약간의 뉘앙스 변화가 전부다. 이러한 구조물들은 투명한 듯 보이지만 다른 한편으로 모든 것을 차단하고 가리고 있는 듯한 느낌을 준다.

2020년에 들어서 고동환의 작업은 이러한 추상적인 형태 뒤에 감춘 집에 대한 자신의 사유를 조금씩 열어 보여주는 듯도 하다.

이번 개인전 <특정한 장소의 불특정한 정체>에서는 기존의 집 모형이 거울의 표면을 입고 등장한 한편, 다양한 입체 모형들이 가구와 같은 크기로 여기저기 배치되어 있다. 모두 바퀴를 달고 있는 이 입체들은 외면에 커튼이 달리거나 욕실 타일이 붙거나 안방의 벽면과 같은 몰딩, 부착물, 혹은 마감을 지니고 있다. 집 안에 있을 때 나를 둘러싸고 있는 집 내부의 것들이 안팎이 뒤집어진 것처럼 입체들의 외부를 둘러싸고 있다. 바닥의 강화마루는 정육면체의 피부가 되었고, 서랍장들은 계단을 이루었다. 이것들에 작가는 ‘특별한/특정한(specific)’이라는 수식을 붙이며, 현실의 사물을 지시하는 대신 삼각형, 큐브, 원, 사각형, 육각형이라는 다면체들로서만 (또 다시) 명명했다. 전시장에서 하루에 한 번 위치를 바꾼다는 이 다면체들은 불안정한 거주에서 늘 바라마지 않게 되는 가변성과 이동성의 소망을 구현한다. 소유의 욕망과 경계의 욕망이 단촐한 형태로 최소화된 이 가구이자 실내인 ‘불특정한 정체’들은 “집은 거주하는 이가 누구인지 말해준다”는 이 사회의 여유 넘치는 통념에 도전한다. 대신, 반복과 노동의 흔적이 묻어있는 이 조각들에서 ‘특정하면서도 불특정한’ 삶의 정서적 흔적은 여전히 봉인되어 있다. 때문에 이것은 누구의 내부가 뒤집어진 것이며, 어떤 이의 욕망이 깃든 것인가라는 질문이 남는다. 가장 사적인 취향과 기억이 깃든 사물, 그리고 그런 시간이 각인된 흔적들은 우리가 흔히 ‘공공’이라고 부르는 허구를 깨고 또 다른 정체성을 출현시키기 때문이다.

My home or stranger’s room

Lee Jin-Sil (Independent curator, Agrafa Society)

Houses which are small like milk cartons are lined up. These houses are made with folded paper boxes, painted using pens of various colors and huddled together in a line. Looking from a distance, they are cute and heartwarming. However, like in a fairy tale, there are no windows or entrances. This is the artist, Dong Hwan Ko’s artwork in 2018, titled

In fact, the theme, ‘house’ is a very obvious symbol and it is a universal metaphor that anyone can project their own narratives. However, looking at it again, there is no other topic as difficult and impossible as home. Usually, ‘house’ and ‘room’ were dealt with at the stage of literature and art, with the start of the modern civil society, which clearly differentiated the public and private domain. In the artworks at the time of the end of the 19th century with nostalgia of the bourgeoisie, a house was lyrical ruins involving the story of collapse where an era came to an end and was littered with emotional debris. With the start of the 20th century, a house became the last shelter for the identity, allowing an escape from numerous activities and relationship, a public domain, and projection of our own taste, desire and habits alone, which is a private space. On the other hand, albeit more importantly; a house is a very contradictory battlefield where ideological fights on women’s position and roles are waged. We are reminded of

Meanwhile, what would be a house to the men living in the same age? A novel, titled

How did we have to read a story of a house without entrances or windows that a young male artist, coming back to his hometown after his study in England, obsessively created? Maybe, the effort to read the psychological structure or context would be a futile attempt. It’s because the artist is trying to assemble the house in various color and materials as if he was a child so indulged in Lego, and the morphological play is not based on such heavy emotions. But, why a house? Ko makes a house in pieces and plane with an attitude as a draughtsman or designer, and it is presented in highly sophisticated and abstract form as if there is no narrative implication or depth in meaning. The geometrical form of the house with a peaked roof on top of hexagonal structure is simple and smooth as if it presents universal concept without any Korean or regional characteristics or specificity. The method of using a character of house is similar. Books that arranged the Korean character, house, repetitively, or a little nuance change in ‘Mi Casa’ would be all. While such structures look transparent, it gives an impression that everything is blocked and shaded.

In 2020, Ko’s work seems to show his own reasoning little by little on the house hidden behind such abstract form. In his artwork,

man, and it is repeated and expanded. Walking through these houses starts with the impression from children’s book such as Neverland with its bright colors, but in the end, it reminds us of a sort of nightmare that we wander around right in front of the house, not being able to find an entrance into the house. We do not know whether this is an anxiety that the place (or relationship), which is deemed as it is entirely for ourselves, would be taken away, or whether it is a shield that strictly guards against others unlike the appearance with hospitality. The entity that says ‘you are here but I am not’ may be the one with no guarantee for a cozy place, just wandering around outside. Or it may be a warrior fighting for its existence that cannot entirely make itself at home even at supposedly the most peaceful place.

The enormous mat with a message

In this solo exhibition,

- 기간

- 2020-11-17 ~ 2020-11-29

- 관련행사